One man sat in the front seat beside Lovingsky while the other got in the back and slid across the seat behind him.

Unusual. He wondered why they didn’t both get into the back of the car like most passengers who used him for a rideshare did. With one beside him and the other behind him, Lovingsky couldn’t help but begin to worry as he drove through the greater Boston area.

He was supposed to be taking them to work but they insisted he follow their directions instead of his GPS.

They went deeper and deeper into an area filled with rows of temporary offices forming paths through an industrial area. The men pointed him back behind a trailer.

“I don’t see anybody. I don’t see any cars passing by,” Lovingsky said about that moment.

He was scared.

Then he heard one of them say, “Sak pase?”

The tension evaporated as Lovingsky gave the traditional Creole response, “N’ap boule.”

The man laughed, saying he thought Lovingsky might be Haitian.

“I asked him, ‘how do you know sak pase?’” Lovingsky said.

The men explained they worked with a Haitian, and he was teaching them a bit of his native language.

Maybe this moment would have made anyone panic, but for Lovingsky, his skin color only amplified that fear.

“They weren’t bad people,” he said before pointing out his own bias. “It was probably because of what I expected.”

The deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmed Arbury, the shooting of Jacob Blake, and the historical violence perpetrated against Black people in this country through the official arms of legislators and police officers; these things weigh on Lovingsky.

Lovingsky Jasmin’s father was one of the boat people. He crossed the Caribbean from Haiti, seeking refuge from the country’s political turmoil in the early 90s. Daniel Jasmin came to the United States with the hope of bringing his family to the U.S. legally. His wife, Josette, stayed behind to raise their four sons, Junior, Ken, Lovingsky, and Nehemie, while Daniel worked towards citizenship and passage for his family.

“I don’t know how my mom did it,” Lovingsky said.

“It was so hard,” he added, his head rolling back a bit as he remembered.

At first, they only heard from their father when he would send recorded messages on a cassette tape. These magnetic messages sustained them as they gathered around the small cassette player to hear Daniel’s voice. The room filled with Daniel’s messages of encouragement and news of what he was doing.

Josette would sing and pray to the little box with its spinning coils of black tape, recording a special message to her husband before calling their sons, “come in and talk to your dad.”

“Sometimes, my mom, when talking to my dad, she would cry and cry and cry,” Lovingsky said.

The cassettes crossed the Caribbean for seven years until Josette moved them to Port-a-Prince. There, they could make phone calls through Teleco, the sole provider of landline telephone services in the country at the time. But, even those had to be scheduled a month or two in advance.

It may have been hard, but Josette kept the boys involved in church. During a special vacation bible school, Lovingsky learned there was more to following Jesus than tagging along on his parents’ faith.

“I learned that even if you were born in church, it doesn’t mean you are Christian,” he said. “You have to make the decision by yourself.”

Apart from the reality of Jesus’ sacrifice and love for humanity, six-year-old Lovingsky also saw the beauty of the community created by those who had accepted the reconciliation God offers through Jesus’ sacrifice.

He loved the ambiance, the friendships, and the relationships he was building with his teachers and everyone around him. “You know that with Jesus, you will be saved,” he said. “But it was very attractive to me to stay in that environment.”

He decided to devote his life to Jesus.

“That was the best choice that I have ever made in my life. To become a Christian,” Lovingsky added.

Those relationships built through his years involved in church, working as a youth pastor, and taking part in a Christian club while in secondary school created avenues for help when he arrived in the United States. But, that moment didn’t happen for nearly twenty years.

Lovingsky’s father worked hard to bring his family over through the proper channels. “The process is so long. Especially for people in Haiti if you want to do it the proper way,” Lovingsky explained.

His dad told him that the suffering he went through coming to the U.S. on a wooden raft and then working and living separated from his family was worth it. It was worth it to give them a better life in the United States through the proper immigration channels.

The process took a long time. “It was so long. So long,” Lovingsky said.

And it wasn’t a smooth transition. The approval process was finalized at different times for each of them. With each successful immigration, the family was further split up. Lovingsky’s brother Ken came over first in 2004, and then Josette and Nehemie arrived in 2005, leaving Lovingsky and Junior back in Haiti.

Finally, eight years later, the two brothers arrived in Miami, and within a week, Lovinsky headed to Boston. He had a Haitian friend with a room and car available for him to begin his new life in the U.S.

The family still hadn’t fully reunited since all of them had arrived in the U.S.

Another friend had invited him to Ohio to stay for a while. But, before heading to Ohio, Lovingsky, his brothers, and his parents were all finally reunited in a joyous celebration at his brother Ken’s wedding. That vein of joy sustained by their faith and love for each other was enough to get them through this long period of separation. Together again, they slipped into the laughter and joking that had always come so easily for them.

A few months after their joyful reunion Lovingsky married his longtime sweetheart Sophia. She was a close friend he met in Haiti through a bible study group in secondary school.

Then, with their son Jeremiah on the way, Lovingsky decided to enroll in Cincinnati Christian University to finish his master’s degree in theology. While there, he felt led to serve in the military as a chaplain and began to pursue becoming an officer. In August of this year, he took the oath of office as a first lieutenant in the U.S. Army Reserve.

In the short time he has lived in the U.S., his eyes have been opened to systemic racial issues. He can empathize with the struggles that are occurring across the country.

“Seeing all that is happening in the country is so frustrating for Black people whether you were born in the US or if you moved to the US,” he said.

Lovingsky speaks with an accent and, at times, pauses as he seems to search for the appropriate words. It would be easy to assume he is unaware of his rights as a citizen, and these traits have not made things easy for him in this country.

“It is even harder for people like me,” he added.

Lovingsky’s interaction with missionaries in Port-a-Prince didn’t prepare him for the reality of the United States. At the mission, he was respected, and he was loved by the Americans who came there to serve.

Since arriving in the United States, he’s had moments of trepidation being pulled over by officers, although he admits besides some rudeness, he’s never had a bad experience. But, he knows the process. Put your hands on the steering wheel in full view. Don’t make any sudden moves. Be polite.

Other times, these moments are unexpected. Like, when someone yells at him to go back to his country or spits on his car as he drives by.

“To see racism in the U.S. is unimaginable; I’ve never experienced something like that in Haiti,” he said.

And it is inherent in the American system – a system that for decades has marginalized groups of people who are not white.

What about those little boxes on job applications? Are you Caucasian; Black, Hispanic, or other? Lovingsky wondered if these little boxes weighed in on an employer’s decision to hire him. He brought it up with a friend who mentioned she would just leave the boxes blank. “Ah, but then they have you,” Lovingsky said. “If you are white, why would you mind saying you are white?”

Whatever you do as a Black person, they know.

But something was different with George Floyd’s death.

Maybe it was the compounded impact of Ahmaud Arbery’s senseless death at the hands of a group of vigilantes, and then the resurgence of the story of Breonna Taylor’s brutal shooting death by police after she was woken from her bed in the middle of a March night.

Maybe it was the eight-minute and 46-second video of a man dying on the ground with a police officer’s knee on his neck.

Maybe the powder keg of racial tension packed full by a president who leaves no middle ground — Americans either revere him or loathe him.

Maybe it’s the pandemic.

Maybe it was George Floyd calling out to his own dead mother as he joined her. The Imago Dei crushed under the uniformed knee.

Maybe it’s that nothing was different about his death. That frustration finally culminating into action as the world watches all these tragic cases and notices that no one — vigilante or officer — is brought to justice or held accountable for their crimes. The message instead is that the killings are justified.

“Seeing all this happen in the country is so frustrating for all Black people whether you were born in the U.S. or not,” Lovingsky said. “I felt I needed to get involved.”

So, he did something.

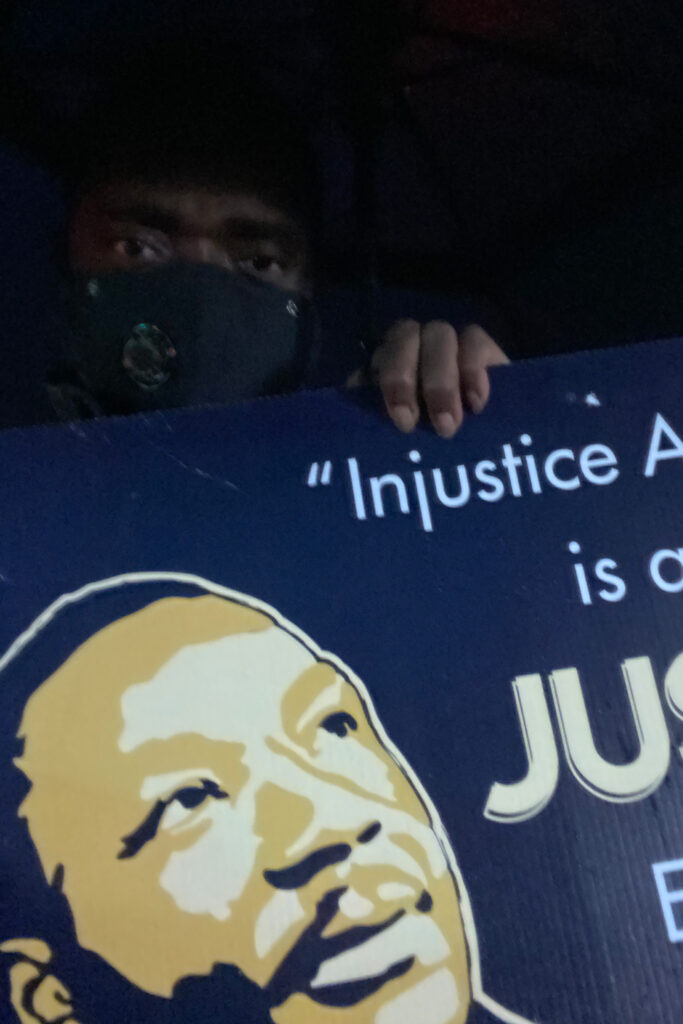

On June 2, Lowinsky voted in Acton’s town election and then stood at the corner of Massachusetts Avenue and Main Street with his son, Jeremiah. They both held “Black Lives Matter” signs.

For a little while, the pair stand by themselves, with Lovingsky proclaiming “Black lives matter” as passing cars honk in support.

“We can do it without violence,” he proclaims on the video he shared on Facebook. “We can teach our children the right way.”

Then more people begin to show up, thanking him for his actions.

A woman walks up and asks if she can buy them dinner. Lovingsky politely declines.

More people show up to encourage them, and Jeremiah charms them.

“I’m Jade,” a woman says as she tells Lovingsky she is joining him.

“Hi Jade,” he says, thanking her for joining him and Jeremiah.

“It started with only two people, and now we have somebody else joining us,” he tells the camera before encouraging others to start their own protest.

About 40 minutes into the live video, several more people walk upon Lovinsky’s three-person protest, more than doubling its size.

By the end of the two hours, he’s got a group of about 10. After ending the protest, they exchange information, and he tells them he will create a Facebook group to keep them informed on the next step.

The next day, the two-hour video has garnered about a thousand views. Lovingsky and Jeremiah head back to the same corner where they meet up with about 500 people who decided to join them.

By Friday, what began with Lovingsky and Jeremiah holding signs on a corner had grown to more than a thousand people rallying together, chanting in solidarity.

That Sunday, a group from a nearby town reached out to him. “They saw what I did in my town and asked me to please come talk,” Lovingsky said, adding they had mentioned they planned on inviting U.S. Congresswoman Lori Trahan, the representative of Massachusetts’ Third Congressional District.

Of course, he agreed.

He and Trahan spoke at the rally, and afterward, they led the march through Westford.

“It was so amazing to see in a town that is 99.9 percent white,” Lovingsky said. “All of them marching with us singing, ‘Black lives matter,’ ‘Black lives matter’.”

Then he was invited to another nearby town, Framingham, to speak and help them organize.

This empowered the growing group to begin attending the local council meetings to bring their voice to the table and seek ways to overcome the systemic biases that permeate our culture. But that is where Lovingsky found the limit for some of his allies on the streets. They would voice their support, but when it came to the hard work to remove or change the systems that ask for a job applicant’s race, they balked.

Appearing in front of his town council to push for reforms regarding housing and policing, Lovingsky realized he lost some of that support. He saw firsthand what has allowed systemic racism to be fostered and then fester within our country. “The system is bad when you don’t include me in it,” he said. “So when you say the system, for many people, it is somewhere else. Washington D.C., or maybe Indiana or Cincinnati, but when you target someone’s hometown with that change, they realize they are going to lose their privilege.”

Reaching into our history, the country’s and the church’s, Lovingsky can trace these contemporary issues back to views on slavery and Black people.

“We are asking for equality. We are asking to be respected. We are asking to be treated as a person,” Lovingsky said, adding that Christian leaders in support of slavery had said Blacks didn’t have souls. “So, they were the same as an animal. That’s why they had the liberty to treat black people the way they were treated because, for them, you’re not a person. I can kill you whenever I want. I can do whatever I want to do to you.”

“When we go down that path, the church has failed since the beginning of the foundation of this country. We have the Bible, and we know what it says, and still, we treat Black people differently.”

W.E.B. Du Bois wrote in The Souls of Black Folk, his celebrated 1903 collection of essays, that Black people lived in a double consciousness —

“‘a sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt or pity … One ever feels his twoness,—an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder. The History of the American Negro is the history of this strive-this longing to attain self-conscious manhood, to merge his double self into a better and truer self. He simply wishes to make it possible for a man to be both a Negro and an American, without being cursed and spit upon by his fellows, without having the doors of Opportunity closed roughly in his face.”

In seminary, Lovingsky had a history professor who always added addendums to his talks on Black leaders in the early Christian church. “He would say, ‘but he was stealing money,’ or ‘but he had many wives,’ or ‘but he was doing this or that’,” Lovingsky explained.

He wondered why every time the professor mentioned a Black church leader, he added the negative connotation. He looked into the white leaders of the early church and found similar activities. “They had different wives, they were pastors, and they had concubines,” he said. “Why didn’t he even mention that about them? Why did he only add that to the Black person?”

Lovingsky is watching those prejudices recede in the people who attend the rallies still being held by the group that formed the day he and his son stood on the corner after voting.

This is the work of reconciliation that Christians are called to take part in. Jesus wasn’t in a building, He changed history by being in the community, creating relationships, and announcing the Kingdom of God.

The Holy Spirit is at work while these people come together. Friendships are formed, and relationships are realized as children play in the grass shadowed by “Black Lives Matter” signs.

“The friendships aren’t staying on the street,” Lovingsky said. “We are texting each other, and our children are friends.”

Those moments of protesting also bring people face to face with the police officers in their community. This breaks down barriers that have been built through the focused perspectives on both sides. “There was a moment during one of our marches in which police officers took a knee with us,” he said.

He invited them to speak to the crowd. Some of the protest group members didn’t agree with allowing the police officers to have a voice in the protest, but Lovingsky saw them as part of the community, not part of the problem. “Some of us never talk to a cop until we have a problem. Sometimes we don’t realize these others, these cops, are also people in our community. They have a family, they have children,” Lovingsky explained.

Also, by hearing police officers speak out about the horrific incidents in our country, Lovingsky hoped this would give the community confidence in its officers. “We are holding them accountable because we now know them, and they know us,” he said.

This is the type of work Christian leaders should be taking part in, according to Lovingsky, who adds that he doesn’t have any problems with church buildings. “But our main job is to go out into our community and do the work,” he said. “Sit with sinners, eat with them, walk with them. Jesus did all of that.”

This has to happen before Christians can invoke change. “Jesus did not criticize them at first,” Lovingsky added.

What started as Lovingsky and his son standing on a corner of Acton has transformed from a place for protesting injustice to a place for creating relationships. Reconciliation comes through relationships. “What we are creating is not just a space for protests, but we are creating a family.”

A family whose commonality is the good that comes through the work of reconciliation that is occurring as people take a moment to hear the voices of the oppressed, the disillusioned, the discouraged, and the broken-hearted.

“I have become friends with a lot of non-Christians. This is evangelism,” he said. “This is the best way to lead somebody to faith when they just see how you act, how you behave, and you start sharing your faith with them.”

Lovingsky’s work has continued, and the group has grown and taken on new challenges. Work that includes pushing for a police reform bill in Massachusetts’ state legislature.

“That is God working; that is nothing else. That is God showing me what he can do for and through me,” Lovingsky said, adding that he is excited about what God is going to continue doing with him. “I am still a working miracle.”

Lovinsky summarized it well in a recent post on social media.

“Despite what the society thought of him, Jesus sat with the marginalized (John 4), healed them (John 9), Invited them to the kingdom of God (Luke 14:16–24), and tore down instead of creating walls of divisiveness and hostility (Ephesians 2:14–16). This is the type of message we need to share and continue to follow.”

Through Lovingsky’s efforts as well as those who have joined him, a new nonprofit, Racial Justice for Black Lives (RJ4BL), has been created. The registered nonprofit’s mission is to raise awareness of racism, injustice, and violence against Black lives, and to advocating boldly for actions leading towards systemic change. The organization’s goal is to create a society that is equitable and just, in which every Black person has the right to economic, health, and environmental security, a meaningful political voice, and a sense of belonging in the community. By working together to create Black joy, we all benefit and we build a community of mutual respect, togetherness, and love. You can contact them by email at racialjusticeforblacklives@gmail.com